Design 54

Imagine dressing up in your finest clothes just to go shopping. Not for a special occasion, but because the shop itself demanded that level of respect. That was Kingsway in mid-20th century Accra - part department store, part status symbol, part monument to a new Ghana emerging from colonialism into independence.

Jamestown Cafe and Gallery in Accra is hosting an exhibition exploring the fascinating story of the Kingsway Stores, the shopping emporiums that once dominated Ghana's retail landscape. Far more than mere shops, these gleaming buildings represented a complex intersection of colonial commerce, post-independence aspiration, and the carefully orchestrated lifestyle curation.

More Than Just a Shop

The first Kingsway opened in Accra in 1915, when Miller Brothers—a British trading firm—decided to create something unprecedented in West Africa: a self-service department store. In a retail environment where goods were typically stored haphazardly in simple buildings, Kingsway was revolutionary. Visitors in 1920 marveled at its separate departments, wide staircases, and the freedom to browse. On the ground floor, gramophones shared space with imported delicacies and 'choice liquids of the culinary arts.' Upstairs, the latest fashions from London hung in a balustraded gallery.

Initially serving the needs of British colonists—offering the 'cultural artifacts of Europeanness' that allowed them to maintain their lifestyle in the tropics—Kingsway would undergo a dramatic transformation. As Ghana moved toward independence in the 1950s, the stores' management faced an existential question: how to remain relevant (and perhaps more importantly, profitable) in a post-colonial world?

Their answer was brilliantly calculated: rebrand colonial-modernist domesticity as elite African modernity. This also aligned with Nkrumah’s vision for a new Accra.

The Architecture of Aspiration

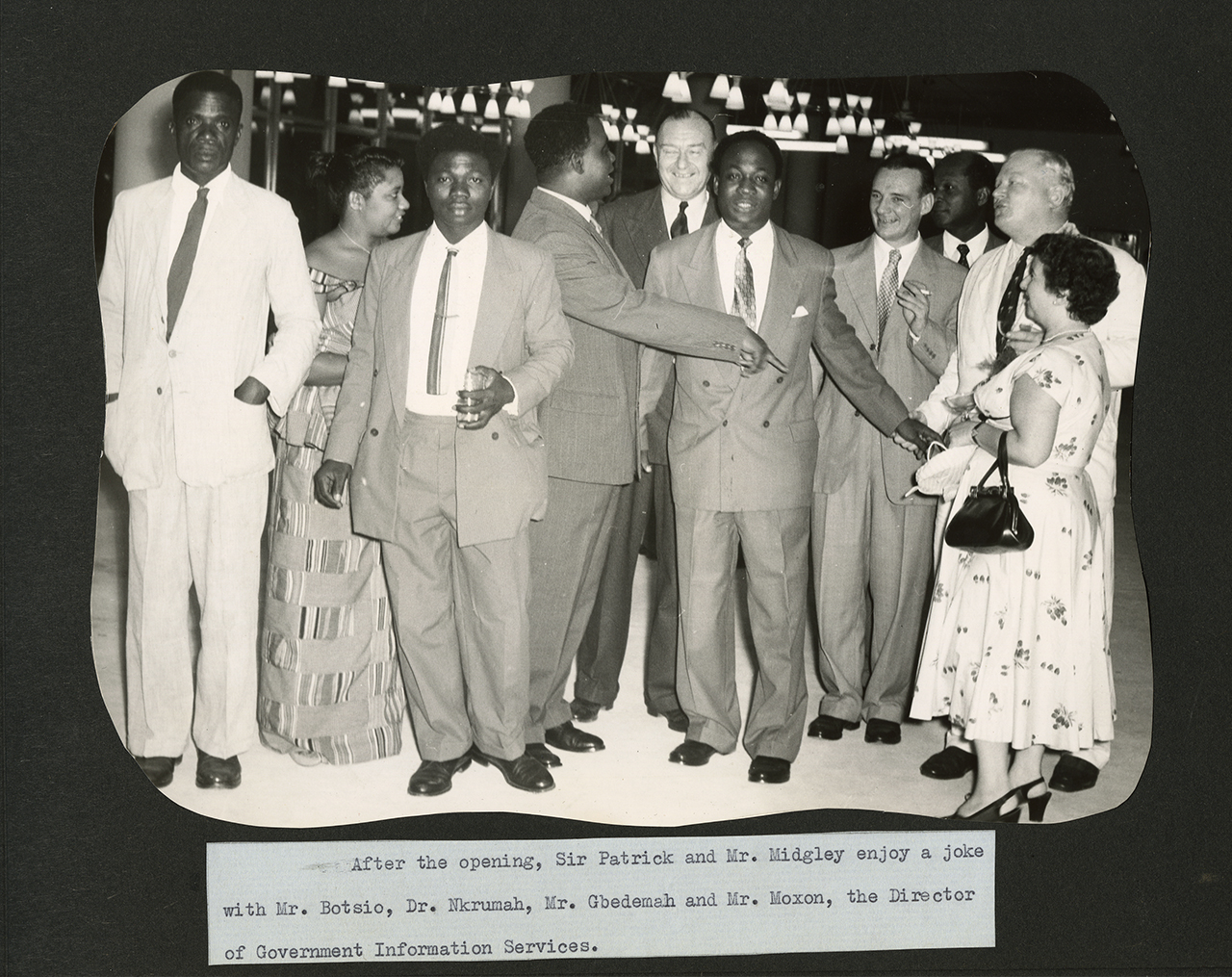

Nothing exemplified this strategy better than the spectacular new Kingsway store that opened on Accra's Independence Avenue in 1957. Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah himself cut the ribbon. The building was a statement—sleek, modernist, unapologetically contemporary. Designed by British architects TP Bennett & Partners, it featured expansive walls of glass held by thin steel supports. The entire building was air-conditioned—a luxury almost unheard of in 1950s Accra.

Inside was Ghana's first escalator. Parents would bring their children just to ride it.The floors gleamed with terrazzo. Upstairs, alongside clothing and homeware departments, visitors found restaurants, a beauty salon, and an international post office. The message was clear: this was a portal to a wider, sophisticated world.

Accra Kingsway Store. Courtesy of Unilever, from an original image in the Unilever Archive.

Selling the Good Life

The stores didn't just sell products—they sold aspiration. Through the 1960s, Kingsway mounted elaborate 'Modern Homes' exhibitions, fashion shows, and demonstrations on 'the womanly art of making a home comfortable, beautiful, sophisticated and smart without heavy spending.'

Eleanor MacDonald, a former spy and pioneering market researcher, spearheaded these efforts. Her exhibitions taught customers about Scandinavian-inspired furniture, British fabrics, contemporary interior design. It was colonial-era 'domestic science' education repurposed for a new audience and a new goal: consumption.

The advertising was sophisticated and revealing. One campaign showed an elegant cocktail party—bejeweled women in elaborate dresses admiring modernist fabric, men in dinner jackets, a uniformed waiter bearing drinks. The furniture was detailed with precision: a sideboard with sculptural plants, a coffee table with splayed legs. The tagline: 'Kingsway leads the way to Modern Living.'

Top: Kingsway Ibadan, Cosmetics Counter, 1968, Courtesy of Unilever, from an original image in the Unilever Archive. Below: Colour photographs of Kingsway Accra from 1958, Courtesy of Unilever, from an original image in the Unilever Archive.

The Paradox of Progress

For many Ghanaians, shopping at Kingsway represented something profound—a reclaiming of dignity, a rejection of colonial assumptions about African 'backwardness.' As one visitor explained: 'Here was a nation where the idea [was] that we are primitive, we are uncivilized... but in that short period of time we really wanted to show the world we are capable of doing things better.'

Yet Kingsway remained a subsidiary of the United Africa Company (UAC), part of the Unilever empire—the same conglomerate that had profited from colonial resource extraction. The stores' modernist reinvention was, fundamentally, a survival strategy. As we argue in our book Architecture, Empire and Trade, modernism as complexly imbricated with colonial and neocolonial profit-seeking.

The beautiful buildings and sophisticated goods weren't gifts to a newly independent nation—they were careful business moves to preserve colonial patterns of profit extraction and ownership.

Why It Still Matters

The Kingsway story illuminates how design and architecture operate as more than aesthetic choices—they're tools of power, persuasion, and identity formation. These stores shaped how a generation of Ghanaians thought about modernity, aspiration, and progress. They represented the complicated reality of decolonization: political independence achieved, but economic structures largely intact.

The exhibition at Jamestown Cafe and Gallery (next door to the first Kingsway) promises to explore these contradictions through archival materials, photographs, oral histories, and design artifacts. It's a chance to revisit a vanished world—when department stores were destinations, when shopping demanded your Sunday best, when a Danish-style armchair or a set of British china could feel like claiming your place in a modern, independent nation.

'Shopping Emporiums of West Africa: The Kingsway Stores' opened on January 15, 2026 at Jamestown Cafe and Gallery, Accra and is currently showing through April, 2026.

The catalogue is available here: https://transnationalarchitecture.group/shopping-emporiums-of-west-africa-the-kingsway-stores/ and click here for Empire,Architecture, Trade – both available as free PDF downloads.